Projects: Development of Intelligence

What assumptions constrain our hypotheses about the causes of others’ actions? Previous empirical work suggests that one key expectation present in infancy is the principle of efficiency— infants expect rational agents minimize cost as they pursue goals. This line of work focuses on two broad questions. First, do parameterized notions of cost underly these early action representations? Second, how does the principle of efficiency support social inference, prediction, and evaluation?

Infants expect agents to act rationally in pursuit of their goals. However, little research has considered whether children expect other agents to learn rationally. In this project, we are investigating 4.5- to 6-year-olds’ reasoning about another agent’s beliefs after the agent observes a sample drawn randomly or selectively from a population.

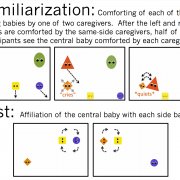

Researchers have made great progress in understanding early human social cognition. Nevertheless, two questions remain unanswered: Do infants organize observed social relations into larger structures, inferring the relationship between two social beings based on their relations to a third party? Second, do infants reason about a network of social relations prominent in all societies: relations of kinship?

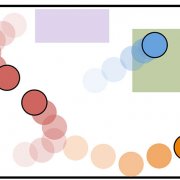

How do young infants represent the movements of others as goal-oriented? In this project, we investigate the degree to which infants' early goal representations include the property of efficiency, and the degree to which they depend on the infant's own past experience with similar motor actions.

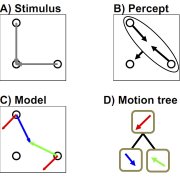

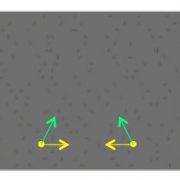

This project explores a Bayesian theory of vector analysis for hierarchical motion perception. The theory takes a step towards understanding how moving scenes are parsed into objects.

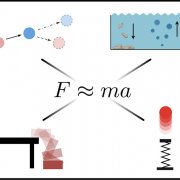

Reasoning about the physical properties of the world around us is a ubiquitous feature of human mental life. This capacity is partly innate, but we can also learn and adapt our intuitive physics, and do so from remarkably limited and impoverished data. This project proposes and tests a model for learning new physical laws and properties.

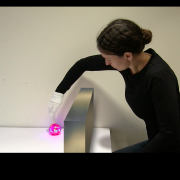

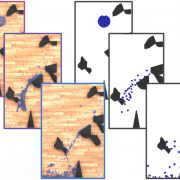

We are developing an online laboratory, “Lookit,” where parents and children can participate in developmental research from home by completing an activity in a web browser while the child’s responses are recorded via webcam. This work aims to mitigate practical constraints on the questions researchers can answer about how children learn by making it easier to collect larger and more representative samples, work with special populations, or run longitudinal studies as needed.

This project explores children's understanding of the geometrical concepts necessary to reason about how the shape of a triangle will change when changes are made to the distance between, or the measure of, the bottom two angles. Past research has shown that children struggle to master these concepts throughout the elementary school years. This project explores the nature of this difficulty and possible underlying causes for the difficulty by examining children's spoken and gestured explanations of their own answers, as well as the impact of providing explanations on their overall patterns of responding. The goal of this project is to characterize children's understanding of the triangle completion task and to develop an intervention that will test possible mechanisms by which it can be overcome.

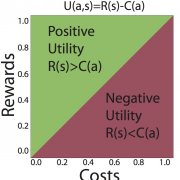

This project aims to understand how humans infer other people’s costs and rewards, and the role these inferences play when we attribute motivational states and when we make social evaluations.

Euclidean plane geometry builds on intuitions so compelling that they were believed for centuries to have the force of logical necessity. Where do these intuitions begin, and how are they elaborated over development? We approach these questions through behavioral studies of human infants, preschool children, and school children up to the threshold of formal education in geometry, together with computational models focused on processes of mental simulation.

Infants develop notions of physics over the first few months of life. They initially have different expectations than adults about momentum, stability, gravitational force, etc. This project aims to find the basic units of physical understanding, using a combination of theoretical modeling and empirical studies.

Humans effortlessly and pervasively understand themselves and others as autonomous agents who engage in goal-directed actions. Some of these actions are directed to objects and cause changes in their physical states. Other actions are directed to other agents and cause changes in their mental states, primarily through acts of communication. This project investigates the emergence of these abilities through behavioral and computational studies of human infants.

With a glance, you perceive whether a stack of dishes is going to topple, a tipping glass of wine is going to splatter on your clothes, or the plate you dropped is likely to shatter. Given the high complexity of the underlying physics of these scenarios and that we do not have direct perception of the parameters involved (mass, density, position, etc.), how do we do this?

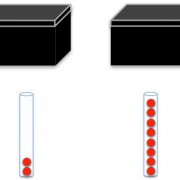

People can report, beforing seeing or hearing something, how well they might be able to identify it -- telling the difference between 2 or 8 marbles shaken in a box is easier than doing the same with 6 or 8. This project studies this ability with young children, as well as what implications we can draw for theories of perceptual and conceptual representation.

Understanding the development of intelligence in a human infant is a key project of CBMM. This project engages the fundamental tradeoff between nature and nurture, or priors and data, and ultimately the origin of priors—how constraints are selected by evolution, encoded in genes, and instantiated in genetically wired brain circuits.

Understanding the development of intelligence in a human infant is a key project of CBMM. This project engages the fundamental tradeoff between nature and nurture, or priors and data, and ultimately the origin of priors—how constraints are selected by evolution, encoded in genes, and instantiated in genetically wired brain circuits.